212: Lucky

EDGAR MARTÍNEZ

Can you PLEASE tell me the area code for Caracas, Venezuela?

The area code for Caracas, Venezuela is 212.

Our school educates, researches, promotes, and shares. "212" is a virtual space focused on photography based in Caracas, featuring the work of both local and non-local artists. This platform aims to bring together various photographic genres, age groups, techniques, and perspectives, all connected by a shared love for photography.

- How did you reach the final edit of "Lucky"? Did you work independently, receive assistance from others, or rely on external feedback during the editing process?

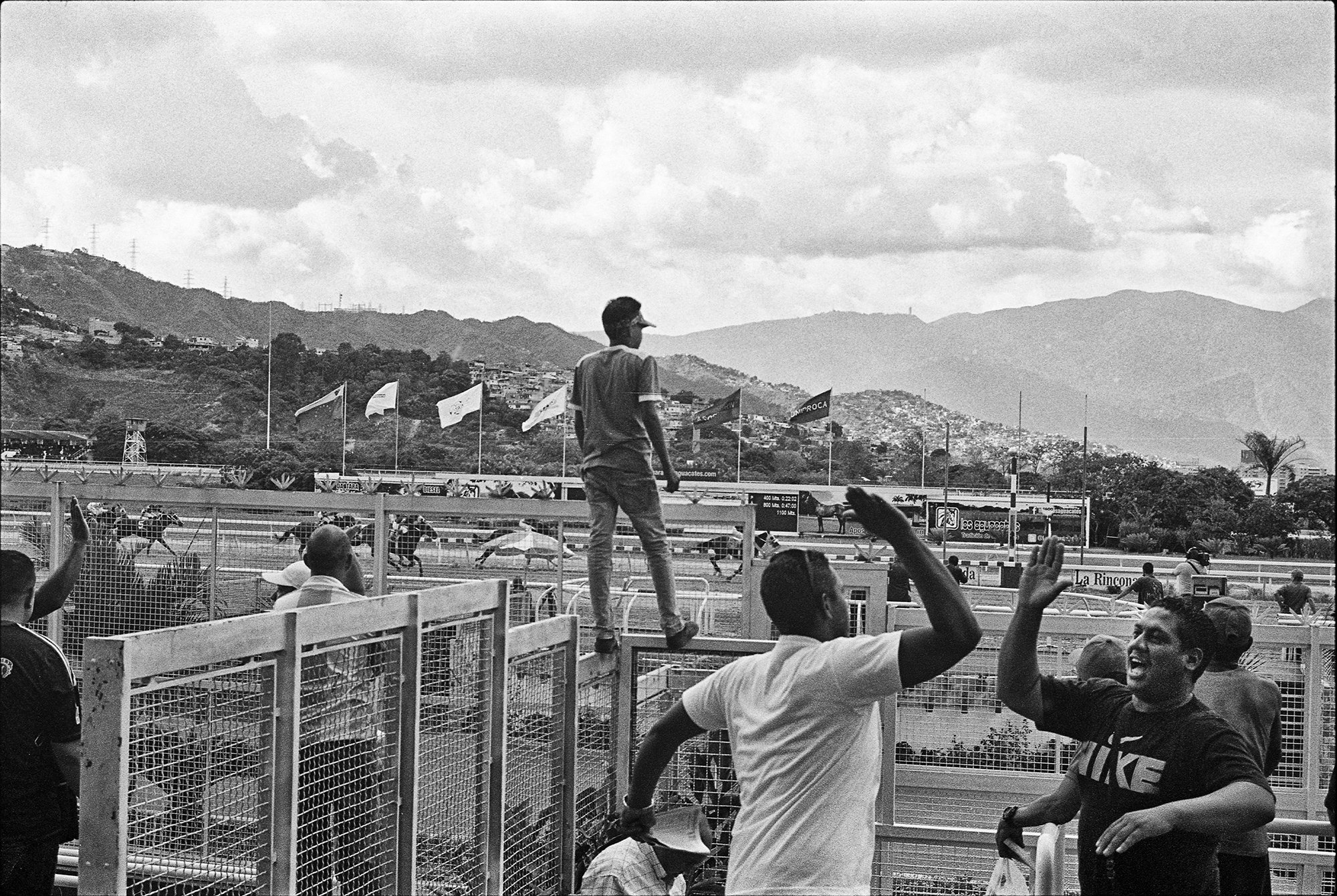

The photographic work was completed over the course of three years (from 2014 to 2017), from which I gathered feedback from various individuals, both within and outside the photographic and cultural realms. This feedback helped me understand the project's message and its direct relationship with the country's narrative. Observing how some impressions changed while others remained constant over time allowed me to reaffirm and discard ideas. Intentionally, I also went against certain viewpoints to establish my own stance. This process led to a completely independent editing phase between 2020 and 2023 for the most recent edition of this work, which I would not label as final. The project was designed as a book (or photo-book), focusing on conveying the message through editorial concepts, narrative editing, design, and texts. The work reflects the tensions of reality: the existence of a shelter within a racetrack that continued its regular activities despite the circumstances, the misfortune of losing everything, and the hope for a new opportunity. It also addresses the prolonged transitional state of those who lived there while waiting for promised solutions, as well as social class clashes within the same space—these contradictions provided essential clues for making conceptual decisions.

- What photographs did you not take or could not take while working on "Lucky"?

I believe that nothing was left undone; I found everything needed in my archive to tell the story visually. However, I recognize that during the project's emotional moments, there was an anxiety to delve deeper, which may have led to missing an image that captures the scale of the temporary housing constructed in that space—an organic landscape where the racetrack faded into what resembled a community. I see it as a sign of maturity to step back and see the situation from a distance. With that perspective now, I can edit the work, keeping a global message in mind. I understand its documentary value over time and recognize that photography is part of a broader visual system that communicates a viewpoint.

- What served as the starting point for creating "Lucky"?

When I began this project in mid-2014, Venezuela was experiencing widespread protests and significant social division. As a photographer interested in these themes, I felt compelled to explore deeper issues rather than focusing solely on the protests as the narrative about the country. I was aware of displaced individuals living in a racetrack since their relocation in 2010, after losing their homes due to severe flooding that year. Media portrayals often contradicted each other regarding state solutions for these victims: some highlighted the negative impacts, while others celebrated supposed resolutions. Rather than engaging in this debate—which overlooked the foundational realities and dehumanized the families facing this life-altering situation—I aimed to approach and understand these individuals on a personal level.

- Did anyone from the Venezuelan state care about your work? Was there any institutional reaction?

So far, I have not had any interactions with institutions or the Venezuelan state, possibly due to the limited promotion of the project. Given our political and social climate, I understand that various interpretations of my work exist; some view it as a struggle between the rich and the poor, while others blame the state for exacerbating issues. Some people see the aesthetic of a dramatic situation that’s part of the reality that we experience as venezuelans and question the photographer's role. There are also those who are unaware of the situation or even that horse racing exists in Venezuela. My intention is not to judge or define positions but to address the lack of empathy I have observed regarding this topic. This genuine concern drew my attention and allowed me access to the personal lives of these individuals. The facts and tensions surrounding them are evident; perhaps naively, I believe that bringing these issues to light will foster reflection beyond political perspectives and encourage an examination of social structures.

- If we were to visit the racetrack today, what do you think we would find?

Today, the racetrack continues to operate as intended without any interruptions. However, it appears to attract less interest, as horse racing has become a symbol of a bygone era for older generations in Venezuela. Of the 2,400 people who once lived in the area, only remnants remain—such as comments about their presence and outlines on the ground marking where their homes used to be.

-Technical details of your work (digital and film). For film: camera, scanner, developer. Digital: camera and optics.

I experimented with various lenses and types of black-and-white film between 35mm and 120mm to learn about technical results on-the-go; however, most of my work was done with a Nikon FM2 camera using a 35mm lens with black-and-white film (mainly Kodak TriX 400 and Ilford Delta 100), developed with Kodak D-76. Additionally, some digital photos were taken with a Ricoh GR used as support along with color film shots taken before formally starting the project. In 2015, thanks to mentorship from Jorge Andrés Castillo, I accessed a lab at the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism at the universidad central de Venezuela where I created contact sheets, small copies of my work, and the final prints on fiber paper. Ultimately, for book editing, the photographs were scanned from negatives using an Epson V700 scanner.

portrait by GABRIELA GAMBOA SANSON

EDGAR MARTÍNEZ:

Caracas, 1986

Photographer and visual artist exploring the life stories that uncover the complex social layers of Venezuela.

Graduated from Pro Diseño (Caracas, 2011) and later returned as a faculty member (2016–2019). has worked in documentary photography, photobooks, editorial design, curatorial consulting, and educational workshops. Shortlisted for Panorama Latinoamericano at the Photo Vogue Festival 2025 (Milan, Italy). Finalist in the Dummy Award 2024 for the photobook LUCKY at The Photobook Museum (Cologne, Germany). Participant in Mesas de Edición – Vol.3 at the Manizales International Film Festival (Colombia). Featured in 10x10’s CLAP! Contemporary Latin American Photobooks, 2000–2016 (New York, USA). Collaborated on socio-cultural projects like Plan B – Caracas Ciudad de Salida (Goethe Institut, 2019), exploring migration’s local impact.

https://www.edgarmartinez.xyz//INSTAGRAM